I never expected that my graduate school experience would include a ride in a C-5A military transport airplane, much less the opportunity to be in its cockpit during a mid-air refueling. But amazingly it did.

In April of 1982 I was part of a team that moved the Crystal Ball, a detector used for particle physics experiments, from Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) in Menlo Park, California to Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY) in Hamburg, Germany. The Crystal Ball was unique among detectors used in particle physics in that it consisted almost completely of a spherical array of sodium iodide crystals and was an excellent tool for measuring the energy of gamma ray photons that can be produced in collisions of high energy particles. The success of the Crystal Ball at SPEAR resulted in an invitation from DESY to move it to the newly upgraded DORIS storage ring in Hamburg. (Some additional detail about the detector itself can be found in my PhD dissertation, starting on page 23 of the linked PDF file.)

Because the Crystal Ball was largely made up of sodium iodide, it needed to continually exist in a temperature and humidity controlled environment. Without this special handling, the crystals themselves would corrode and be worthless for experimental purposes. In addition there were concerns about it encountering excessive g-forces (i.e. sharp jolts) that might crack one or more crystals. Ultimately it was decided that instead of sending the most delicate portion via cargo ship, it would be transported by a C-5A military transport plane.

The heart of the detector was carefully packaged into special boxes constructed with a styrofoam cushion against shock and which allowed the flow of dry nitrogen to control the humidity. These boxes were loaded into a specially outfitted US shipping trailer and trucked to Travis Air Force Base northeast of San Francisco. The trailer itself was loaded into the C-5A and detached from the truck which stayed behind.

The cargo area of a C-5A is massive tube. Here’s a photo prior to the trailer being loaded.

Prior to the flight we got a tour of the cockpit and I got to take some photos. This was as close as I ever expected to get.

There were a couple of unusual aspects to flying in the passenger portion of the C-5A. For improved safety, the seat backs are in the direction of travel. At first this seemed odd but once you could no longer see out it really didn’t make any difference. And the windows themselves were either non-existent or were so high up that you couldn’t see out of them while seated. The biggest issue while flying was that it was LOUD. We all were given earplugs to wear during the flight but even with them it was loud. No doubt it was the most claustrophobic and uncomfortable flight I’ve every taken. But also the most incredible.

We took off and after a few hours there was going to be a mid-air refueling. I don’t know if that was strictly necessary or was done so that they could practice the process. Either way it was incredibly exciting because our team from SLAC was invited to the cockpit in groups so we could watch!

When I got to the cockpit, this was the scene I saw.

After a short while I got to locate myself just behind the pilot’s seat, to the left of his left shoulder. And what I saw startled me at first. Flying at our speed, just above and in front of us, was another airplane. The photo below was taken through the left side of the windshield in the cockpit and you can clearly see the boom that was already attached to our plane, providing fuel. I don’t know the distance between the two planes but it could have been as close as 20 feet and almost certainly wasn’t more than 50. Let’s just say it was close.

Below the boom is a window where the boom operator in the other plane can see our plane and properly guide the boom. I was able to take a photo where you can see the boom operator’s face through that window.

Once the refueling was complete, the boom was withdrawn and the other plane slowly flew away from us.

Once it got a sufficient distance away, the fins on the boom became visible.

What an amazing opportunity! It was an unforgettable experience to be in that cockpit. And I can’t believe that I got to take photos.

Once we’d taken off, the landing was the next risk point in the journey. Because large g-forces could be damaging to our cargo, we’d equipped the trailer with recording accelerometers so we could monitor the conditions. I’m not exaggerating when I say that it was the smoothest landing I’ve ever experienced while flying. We landed safely and encountered no problems with the detector.

Here’s a photo of the trailer being safely unloaded from the C-5A. That’s me with the red backpack on the right side of the photo.

They took a group photo of the flight crew plus our team. The civilian team was led by Dr. Ian Kirkbride from Stanford and Dr. Don Coyne from Princeton. Chad Edwards (now at JPL) was a Cal Tech graduate student at the time and is the redhead at the bottom-left in front. I’m at the back with my hair flying, sandwiched between two air force men. Other members of our team were Jim Nolan, John Hawley, Bob Parks, and Sal Fazzino. (Apologies to anyone I left out or whose name I got wrong. It was almost 32 years ago!)

Now all we had to do was drive from where we’d landed at Rhein-Main Air Force Base in Frankfurt to our final destination in Hamburg. But there was a surprise in store for us.

During the drive from Frankfurt to Hamburg we took turns traveling inside the trailer, riding with the crates holding the Crystal Ball hemispheres. The idea was to ensure that the environment was being maintained during the trip. At some point along the drive I was in the windowless trailer when the truck unexpectedly slowed down and stopped. The truck had blown out a gasket or thrown a rod and that was going to require a major overhaul. That didn’t seem like too big a deal until we found out that there was only one other truck in Germany that could pull our trailer. Apparently the coupling needed for pulling an American trailer was rarely available. It’s safe to say that there was a lot of confusion when the breakdown occurred. I think this photo captures that.

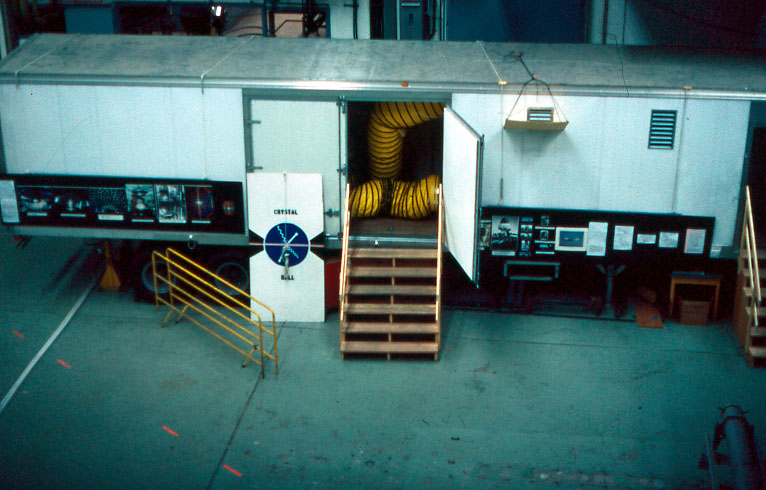

In truth, the remainder of the trip went smoothly. The replacement truck arrived the following day and we were able to transport the trailer containing the Crystal Ball safely to its new home at DESY. Here’s a photo of the trailer after the Crystal Ball was unloaded from it at DESY.

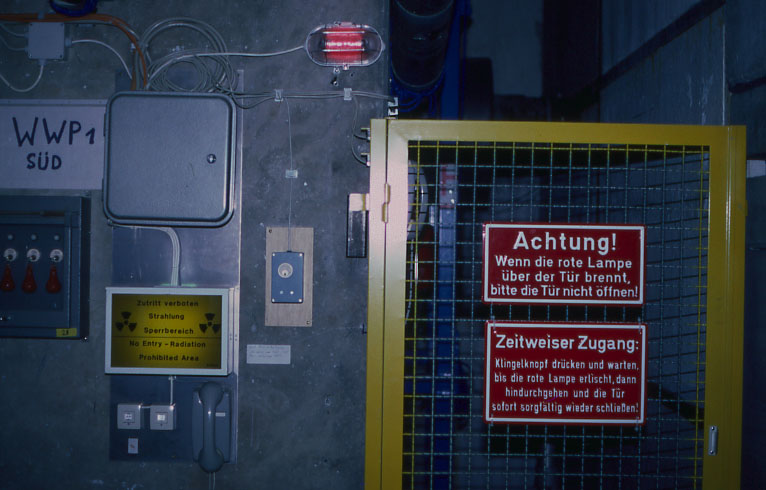

And the Crystal Ball was installed inside the radiation area where the beams collide.

It was all quite an adventure. And one of my fondest memories from graduate school.

January 13, 2020 at 6:47 pm

David,

I very much enjoyed this blog entry. Thanks for sharing! My dad, Charlie Peck, proposed the Crystal Ball detector with Elliott Bloom, his very good friend and fellow physics professor at the Caltech High Energy Physics Dept, in the mid 1970’s. Their proposal was granted funding, and construction started in 1975 at the machine shop at Stanford Linear Accelerator Center. I was fortunate, my dad hired me on as a Techie grad student even though I was just 16 and in high school at the time. He was very patient and let me help assemble and test the CB in the summers of ’78 and ’79. I cleaned each of the 2.5 inch round glass windows after SLAC received the assembled hemispheres from Harshaw Chemical, in Cleveland. I then mounted most of of the photomultiplier (PM) tubes on the two hemispheres for the first time, and set the gains on each tube using a small radioactive source taped inside the inner hemisphere. Each of these tubes is housed in a black aluminum tube about 3.0 inches in diameter and 10 inches long. Charlies hand writing is on each of the yellow labels wrapped around the base of each tube. There were about 750 PM tubes. Each one had 5 connections: high voltage in and out, signal out, and LED and fiberoptic test illuminators in. This assembly occured in the SPEAR e-/e+ storage ring at SLAC, in a dry room. It was nice in there, dry and cool during the summer in the south Bay Area humidity! Perfect for working on a digital oscilloscope fiddling with PM tubes. I never saw the detector in operation, but I heard many tales, such as the visiting party of dignitaries from the other side of the world; someone accidentally set off a fire alarm or something, and all these distinguished visitors scrambling all over the place, hiding or fleeing. I believe the detector was active at SPEAR/SLAC from 1979 to 1982. The data looked good, the findings promising, so they moved it to a more powerful accelerator at DESY in West Germany. Crystal Ball was the first such optical detector with high solid angle detector coverage, the first of a series of every larger such detectors. My dad Charlie worked countless hours on this device, and was very pleased with it, and proud to know it was still being used to collect physics data when he passed away in Pasadena in 2016. It was one of 3 significant detectors my dad worked on in his 50 year career at CalTech (that I can remember: Crystal Ball, MACRO & MINOS) as part of the “small group” of high energy experimental physicists: Barry Barrish, Elliot Bloom and Frank Porter. Thank you for helping to safely move the Crystal Ball over the Atlantic Ocean! -Brian Peck, Reno, Nevada

January 18, 2020 at 12:57 pm

Thanks Brian for adding information about the history of the Crystal Ball. I simply don’t remember if I ever met your dad during those years long ago. I do remember his name mentioned many times.

By the time I worked on the Crystal Ball (1981-85), Elliot Bloom was already working at SLAC and was no longer directly affiliated with Cal Tech. Frank Porter was the Cal Tech scientist I recall the best and he was not only a stellar physicist but also was a great person to work with. Chad Edwards was a Cal Tech grad student working on the Crystal Ball and he was also on the flight to Frankfurt, and is pictured in the group photo in my blog post.

December 28, 2016 at 8:49 am

Dave, Great story I was one of the young AF Loadmasters on this flight and remember how excited everyone was to get the ball on the ground in Germany.

December 28, 2016 at 12:03 pm

It is so cool to hear that you were there. It was really a special experience for all of us involved with the experiment.

November 17, 2014 at 4:13 pm

Hey David! I don’t think I knew you then, but John Hawley and I painted the “Crystal Ball” sign on that big piece of wood that you show in your pictures next to the trailer! John flew on the C5, I was there for an early shift just reading thermometers (I was just a technician then with a BS working for Don Coyne and Matteo Cavalli-Sforza … I see both Don and John in some of your pics). It was so cool to find your pics! I am giving a talk tomorrow and want to talk about early career work I did.

November 17, 2014 at 7:36 pm

Richard, I remember your name but after all this time I don’t remember more. Glad you found the photos. It was definitely an amazing trip.

January 26, 2014 at 9:08 pm

I want to thank David for the special favor. It means a lot to me and he came through like a champ.

January 26, 2014 at 6:21 pm

Dave…Im the driver taking it off the galaxie at rhein main from the 78th trans co……did you get or do you have any other pics? By the way…I had the stars and stripes front page and lost it. I almost had a stroke when i saw this. I have been looking for years.

January 26, 2014 at 8:19 pm

Amazing that you found my blog post! I hope you like the photo of you from so many years ago!

January 17, 2014 at 5:35 pm

Fantastic story about what must have been an incredible experience. You never cease to amaze!

January 15, 2014 at 6:43 pm

I so remember this! You sent me or showed me the pictures. They are vivid in my mind. I did not recall how fragile the Crystal Ball was. 32 years ago! Yikes! Sally

January 15, 2014 at 5:52 pm

What an incredible experience from start to finish!